Hey! Hello! Long time no see. I’m James, and welcome back to Book Brat! I took two months off for no particular reason other than I didn’t really have anything I felt the need to write about. I will pretend, however, that this was thematically relevant to the books I want to talk about today, in that we can act like we were all on summer break. Hope you enjoyed yours, it’s time for the new semester.

Across five years of bookselling, I have recommended Elif Batuman’s 2017 novel The Idiot more times than I can possibly count. It seemed to fit nicely into whatever situation that I needed it to, and I was able to recommend it freely, and frequently, based on the customer’s needs. Need a book with a love story? This has that. Looking for a campus novel? This is the one for you. Need something pleasant to read at the beach? Here check this out, it’s nice, but it won’t make you feel stupid.

In 2022, five years after its release, and five years after I started to recommend it to people, I finally read The Idiot for the first time (buried the lede a bit, I’ll admit it). Thankfully, I was right about all of the above promises, so I was not a complete liar (at least about this particular book) but I also realized that, unbeknownst to me, The Idiot possesses a real emotional depth. So much was made about how smart the book is—a campus novel that takes place at Harvard, before going off to do a semester abroad. It was frequently described as “a novel of ideas,” which is true, but it’s more than that.

It wasn’t until I was about 17 pages into Either/Or, the direct sequel to The Idiot, that I realized what Batuman was doing, at which point I retroactively gained a level of understanding and appreciation of the book I had just finished.

At the outset of Either/Or, Selin, our dear naïve protagonist, has just arrived back at Harvard for the beginning of her sophomore year. She’s still reeling from the fallout of her freshman year, and the ensuing summer (we’ll get there), and she’s looking for answers. At the campus bookstore, she picks up secondhand copies of Kierkegaard’s Either/Or, and Andre Breton’s Nadja, and she says, offhandedly, “it seemed possible that one or both of these books might change my life.”

And it was a particularly satisfying lightbulb moment because, well, I was that same kid—19 years old and searching—and holy shit did she nail it.

Batuman has been entirely upfront about the autofictional qualities of these two novels. Her first book, The Possessed, was nonfiction, as evidenced by its subtitle: Adventures With Russian Books and the People Who Read Them. In The Possessed she tracks (often literally) the evolution of Russian literature and its fans. But there was one fan of Russian lit that really stood out: herself.

And so she wrote a novelized version of her own life. Continuing her very very funny commitment to making her books difficult to Google, she titled it The Idiot, mostly because she thought it was funny to write an autobiographical novel called The Idiot, but also to once again share in a name with Dostoevsky. She says that she felt that Selin’s cluelessness was the interesting and valuable thing about the story, so she decided to write in the “unmediated” voice of an 18 year old.

The book is funny. It’s dry, and ironic, but never really at anyone’s expense. If the joke is that someone is uninformed, or pretending to be something that they’re not, it never lands as mean-spirited because, well, everyone is uninformed and performative at 18.

Selin arrives at Harvard in the fall of 1995, and is almost immediately overwhelmed by the impossible scope of the things she does not know. For example: email (or e-mail, in that very 1995 way), which Selin knows is going to be an important part of her life, but she still finds intimidating.

The (admittedly niche) joke that I liked to make was that an alternate title for The Idiot could have been “Love In The Time Of E-Mail,” and so enters Ivan.

Fuckin’ Ivan.

Where even to begin?

Ivan is Hungarian, and Selin meets him as she’s shopping classes for the fall semester. She meets him in a Russian class, they talk about the linguistic overlap between Russian and Hungarian, and they exchange information.

Watch your step as you proceed here, because if you look down, you’ll notice the poignant metaphor—the fact that Russian and Hungarian overlap, but only just-so. They can’t fully understand each other, not really. Just enough to get by.

Selin and Ivan stay in contact, mostly through e-mails. Doing the inelegant dance of “the other person waited a day to message me, how long do I need to wait, even though I want to talk to them?” They rarely see each other in person, but when they do, the gap between them is apparent. Ivan is a mathematician, and older than Selin by several years. As a part of his grad-school program, he sometimes teaches the classes, he doesn’t just take them.

The year winds on, the two grow closer and closer together, and it becomes…intense. They never really do figure out what they are to each other. It’s a complicated dynamic. They talk constantly, but rarely in person. They’re much closer than the casual friend, but they’re not explicitly romantically involved—a fact really driven home by the existence of Ivan’s girlfriend. She has a PhD, and is twenty six. How can Selin possibly compete with that?

Ivan pushes Selin, not in a bad way, necessarily, but he definitely pushes her. He leads her on, bringing her into these tender emotional exchanges, only to remind her how out of reach he is. Ultimately it concludes in Selin following Ivan to Europe, where she’s going to teach English in Hungary, a program she applied to in an attempt to be closer to Ivan when he goes home to visit his family.

It doesn’t work out.

The two of them crisscross through Europe, as they endure the mess of breaking up with a person with whom your relationship has never been defined. Ultimately, Ivan goes to study mathematics in California, and Selin returns to Harvard.

The book ends on a sad note, with a particularly devastating nod to Green Eggs & Ham, and the Dr. Suess shirt that Selin wears throughout (if you’ve read the book, you know what I’m talking about. If you haven’t, I won’t spoil it).

And then Either/Or is like throwing open a window, letting in light, and sound, and fresh air.

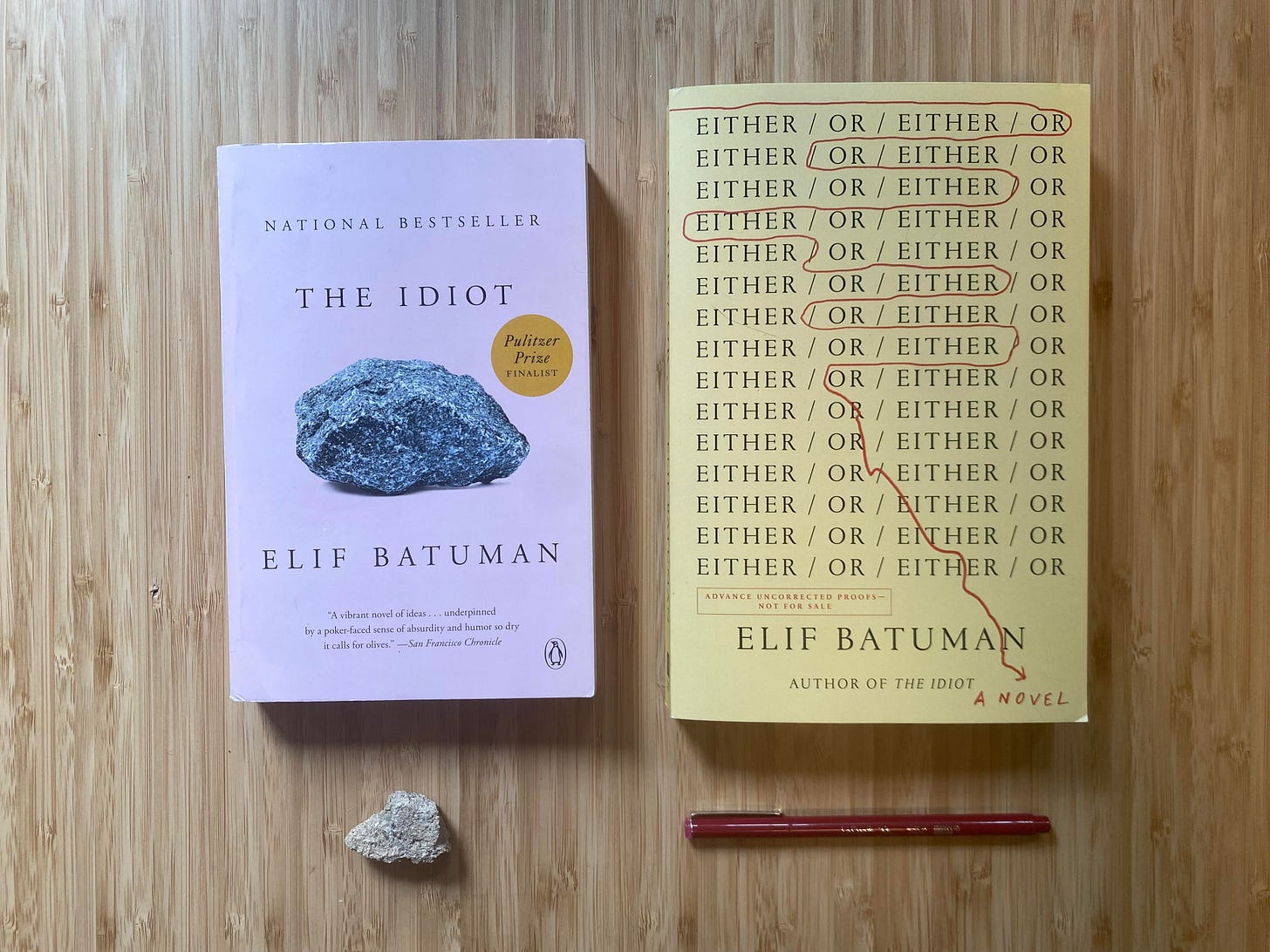

Picking up from where The Idiot left off, almost to the sentence, Either/Or is a rare thing: a Literary Fiction sequel. It’s one that absolutely earns its existence, rather than being some kind of cash-grab, because we are treated to Batuman’s incredible talent for observation, now applied to a whole host of new themes, ideas, and situations.

Where The Idiot was almost suffocating in its one-on-one dynamic of mutual obsession, Either/Or is the opposite. As a sequel, it does everything that a sequel should do: throwing familiar characters into bigger, more interesting situations within the world you’ve established (in this case, Harvard in 1996).

Either/Or is a social novel, greatly expanding the cast of characters, and the number of different environments Selin finds herself in. For example, Batuman has said that one of theme of the book is “how horrible it is to go to parties” and go to parties Selin does. Parties thrown by friends, by acquaintances, by the campus literary magazine. And largely, she hates it! She abandons one by just saying “Sorry I have to go read a book.” To which someone remarks “these things can’t wait.”

And the thing is, as irrational or fictitious as Selin’s behavior can seem at times (you followed this boy to another continent???) it tracks as the actions of a young person on their own for the first time. You’re going to make some mistakes, but they’re your mistakes.

When I was 19 years old, I moved across 5 states for a girl that I knew (mostly) through the internet. We saw each other a number of times you could count on your fingers, talked online and via text constantly, and then the next thing I knew, I had packed my childhood bedroom into a U-Haul and was headed for Brooklyn.

It didn’t work out.

Then, like Selin, I was 19 when I first picked up Kierkegaard (Sickness Unto Death, Penguin Classics edition) and Andre Breton’s Nadja (edition unknown, I got it from the library) in the aftermath of this thing that I had let rearrange the entire landscape of my life. I was trying to figure things out—who I was, what the world was like, why I was doing the things I was doing—and I thought that minds that history had venerated could explain it to me.

Selin is going to all these parties, meeting all these new people, as a way to try to affix a label to herself. She, like all 19 year-olds, has struggled to find out who she is, so now she is looking to be told, instead. Influenced by Kierkegaard, Selin sets out to try to live an “aesthetic life” the way that some people are Young Democrats, or Post-Marxists, or are on the student council. One particularly memorable partygoer agonizes over whether or not she’s “a smoker,” obsessing over her habits, asking, publicly, for others to help define her.

It’s always going to be easier subscribe to an established label, or belief system, and say “I am this,” than it is to contend with the shifting multitudes that we all happen to contain.

In the end, Kierkegaard’s religious dialectics turned my teenage brain into mush and made me feel like I had a head cold, but the experience remains an important one in my mind. When you’re out there, alone, feeling around in the dark, everything you come across—everything that you bump into and try to surmise the shape of—feels significant. All your relationships, both platonic and romantic, are going to be super intense. Everything seems as though this is the thing that makes it all make sense. It’s just a part of the arc of human life.

There’s an urgency to being nineteen that I think fades as a result of that same urgency. When you spend so much time trying to get your hands on as much of the world as you possibly can, it’s easy to become jaded when you then come to see the world.

The real miracle of Elif Batuman’s novels is that she never forgot that feeling—that urgency, that excitement. The Idiot and Either/Or are both tremendously enjoyable novels, but they will stay in my mind as an invitation to reconnect, to hear the echoes of a younger self, just as Batuman was doing when writing them.

Everyone deserves a summer break from Substack. I, er, very intentionally take one every year… The Idiot has been on my list for a while and I’m inspired to pick it up finally. I do want to read it purely, though, so I saved this post and will come back to it when I’m done with the book. ✨